Part II. No Light at the End of the Tunnel

An invasion or a massacre, the departure of illustrious figures from the public scene, the desuetude of arts and institutions vaguely reminiscent of our own, or some dismal manifestation of centralized Authority in the name of a metaphysical or political mystique—any of these phenomena can usher in a period of unwritten, though clearly miserable, history. At the risk of bathos the statement must be made: no matter how dark the age or contradictory the reports that sweep it off the map, it remains inhabited by people.

For us the glittering but finally melancholy ancient world founders and dims into a noiseless though disquieting emptiness, to which (before we hurry on to think of something else) we give the passepartout term: barbarian invasions.

Barbarians are nice because we don’t know anything about them. It’s true that Corinth had been levelled in 146 BC and Athens sacked sixty years later by the rude legions of a people emerging from obscurity; but Roman civilization was to last another six centuries, and many of our modern institutions derive from it: republicanism; colonialism;*imperialism; senates; dictatorship (permitted for a limited period in special emergencies); the languages of Europe; law; nostalgia for a clumsy but innocent and honourable past; blind devotion to an ill-digested classical Greek culture; and the concept—at least the concept—of political probity, which can give such impetus to the reality of political hypocrisy. There were barbarians in Athens in AD 267 and throughout most of Greece in 395, but it wasn’t till the sixth century, after the reign of Justinian—for all the walls he built—that Slavic barbarians overran the country, and from then on for the next three hundred years the rest is, historically speaking, silence.

Fallmerayer’s assertion in 1830 that the latterday Greek race has no lineal connection with the ancient, is mainly notable for the diplomatic flutter it produced in a Europe alarmed at any incentive to Panslavism and Czarist Russian expansion. The statement was based on three reliable but by no means conclusive medieval sources: namely, a letter from a Patriarch to an Emperor around the turn of the eleventh century, to the effect that for two hundred and eighteen years not a single Greek could set foot in the Peloponnese because it was held by the Avars; a sentence in a mid-tenth-century history stating that after the plague that decimated the Peloponnese in 746-7 the land was completely in the hands of the Slavs; and the report of an eighth-century pilgrim who, landing on the Pelopon-nesian coast locates it ‘in Slawiniae terra.’

Yet it is ethnically impossible (plague or no plague) for any one set of invading people to obliterate an indigenous population. In Antiquity the Helots were more numerous than their Spartan overlords, which was why Spartan rule was so jumpy and ferocious. Time without number China has been invaded, but it has never been conquered. Greece ditto.

And what do we really know. ethnically speaking, about the ancient Greeks? They were a mixed lot—about as mixed as (for all their insularity) the British, with their Britons and Angles and Saxons and Celts and Picts and Scots and Normans and Danes—to say nothing of the mixed populations of Russia, America or China. And the question of who exactly were the ancient Greeks can arouse some of the fruitiest loathing in the heart of one academic specialist for any other academic specialist. Totter is angry with potter, and beggar is jealous of beggar, and minstrel hates minstrel’—the truth of Hesiod’s dictum is nowhere so evident as in the groves of academe. What makes a nation anyhow? What, specifically, has made the Greeks? Though they have never been a people to admit foreigners gladly (which may have been why they assigned foreigners to the special protection of no less than Zeus), it was nevertheless the Athenian Isokrates in the late fourth century BC who made the generous assertion that ‘Greek is the name given to anybody who takes part in our form of education and shares our culture.’ Later it was a fragmented Greece that slowly absorbed the mighty Romans, or, as one of their own poets observed, ‘led captivity captive.’ And after that, in the dark of history, it was the unaccommodating Greek terrain (‘mille fois plus sauvage que toutes les Turquies, ‘wrote a French traveller in 1851), the rough and unrewarding soil, the quantity of other tiny lands close by that could only be reached across one of the most treacherous of seas, the desert heat, the Alpine snows, the exhausting dryness and the perilous damp, the intense and unforgiving traditionalism of a people who had become Greek either centuries or millenia before—factors like these often made the invaders Greeks through the fierce process of survival by assimilation.

Particularly was it so under that theocratic imperium over innumerable tribes and nations, enthroned in a distant capital that was the only city in Europe (Paris, Rome or London barely existed outside their fortress walls), with theology and civil law radiating and pumping out from under the world’s hugest dome, in the city straddling the trade routes of a hemisphere:—a city where castration was the quickest way to bureaucratic promotion, and both administrative punishment and the aftermath of usurpation (even by mothers, brothers, sons against each other) was the blinding of the ousted. This was the orientalized Helleno-Roman-Christian world of Byzantium, and everybody in it was accounted Greek by reason of obedience and faith.

Often it lost; steadily it shrank—but steadily over a thousand years. And territorial Greece meant almost nothing. One tidal wave of barbarian invasions or one little band of roaring adventurers after another engulfed it time and again. Where are they now? What happened to any of them? What mark did they leave on Greece or on the life of the indigenous and defenceless? Roman law, yes, and a few Roman ruins: a smattering of Slavic village-names along the flanks of Taygetos in the Southern Peloponnese; a gothic arch in the little town of Andravida, south of Patras; a gothic chapel in the heart of the Morea; a few Roman Catholics with resonant medieval Italian family names in the Cyclades; a few Venetian titles (jealously guarded) in the Ionian Islands; an admixture of recognizably Italian or Turkish words to the language; an early Albanian dialect in Attica and on Hydra, Spetsai, Aigina and Andros; a dialect akin to Roumanian in the Pindos Mountains; fortresses all over the place, built (often on classical foundations) in order to subjugate the local population; and finally—(more elusive, and appearances to the contrary, but more of a living force than any of these scattered traces, and for good and bitter reason deeply implanted in the folk-consciousness of the race)—hatred of foreigners.

The betrayal of Greece by foreigners in league with local time-servers dates back to Rome. And the story would seem repetitious to the point of monotony if it weren’t every time so devious. Easier to follow is the chain of events in classical Antiquity, because of the independence and still clear-cut differences between the protagonist nations: Thebes with its illustrious mythology (Oedipus, Antigone, etc.) that nevertheless sided with the invading Persians; democratic Athens drawn with fearful inevitability into an imperialistic policy that brought about its downfall; Sparta the militaristic oligarchy jealous of Athenian power and the attractions of democracy; Corinth the businessman of city-states, trying to hold a balance of power despite a similar jealousy; Macedon a military but enlightened imperialism; Rome (that learned enlightenment from one of its subject peoples), imperialistic first by treaties of friendship and protection, then by arms.

Medieval Greece is enough to drive the historian out of his wits or make him ramble. Partly because of the absence of ideology other than the hair-splitting sectarian, partly through the quantity of feudal states that succeeded or tangled with each other on its soil, and partly through the very size and internal diversity of the theocratic empires involved: the Holy Roman Empire, the Papacy and Byzantium.

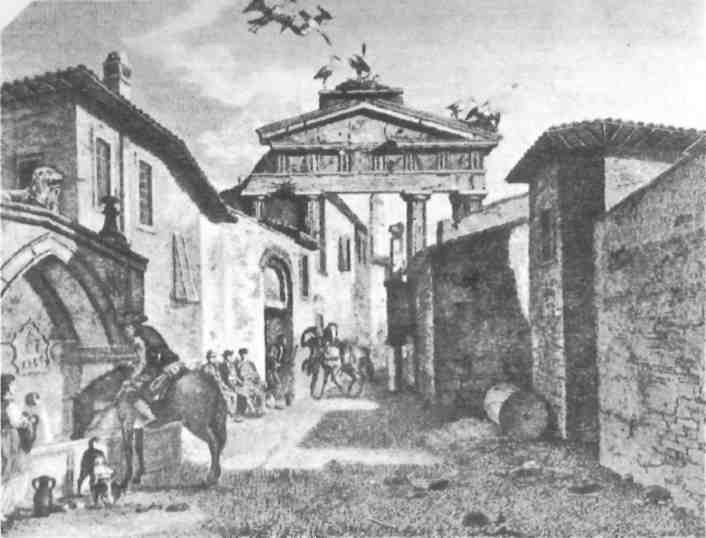

Yet there does remain one guideline—even if one’s still trying to peg a compressed view of medieval Greece to two cities that had become two fortresses: the Acropolis of Athens seat of a feudal Duchy changing hands from one set of Western European warlords, mercenaries or merchants to another; and Corinth the key to the Peloponnese, a Frankish Principality — with Venetian trading – stations at strategic points along the coast.

But we begin with six or seven centuries of almost total poverty (though the skilfully decorated monas-teries of Daphni and Hosios Loukas show there must have been a bit of money somewhere) in a sumptuous empire’s most abandoned province. Then century follows century with that same land a pawn in the long-drawn death-battle between the Eastern Orthodox Empire and the rising feudal and commercial states of Western Europe; with the Papacy behind them ravenously extending its military and economic dominion over an area of Christendom slightly alien in ritual and doctrine, but possessed of riches and relics, territories and trade-routes unlike anything in the West.

After the fourth century AD, certainly after the total suppression of paganism and the closing of the schools by Justinian, nothing is known specifically of Athens for nearly seven hundred years, except for one briefly recorded incident in 1018. The fact that the Emperor Basil II made his way back to Constantinople from his final gruesome campaign against the Bulgars via Athens where ‘he gave thanks to the Mother of God and adorned her temple with many fair and costly treasures’ does not argue for anything very notable except that the Parthenon was functioning as a cathedral and considered worthy of an Emperor’s generosity.

The misery of Athens toward the end of the twelfth century is recorded at length in the despairing pages of one of its archbishops, Michael Akominatos of Chonai, who laments the atrocious dialect, the faithlessness, the boorish ignorance of its inhabitants, and the havoc continually wrought by pirates based on Aigina, and the merciless extortions of the tax-collectors from Constantinople.

Corinth was prosperous by comparison; the Arab geographer Edrisi and the Hebrew traveller Benjamin of Tudela both note the commerce thriving in its two ports on the Corinthian and Saronic Gulfs.

It was an age however when life can’t have been happy anywhere. When we read in the acheing pages of historian’s prose that on such and such a date this or that fortified place fell to this or that military commander, we are not told of the huge sacrifice of the attackers’ lives, or of the panic of the defenders’ families, or of the massacres that followed victories. The dry chronicles of the time give little picture of the horror of existence when, for instance, in 1147 the great citadel of Acrocorinth was captured by the Norman King of Sicily, Roger II. Easier for us to grasp is the quietly economic fact that, in return for their well-timed assistance against the Norman scourge of the Mediterranean, the Venetians were granted special trading privileges in Corinth and other cities of the Byzantine Empire.

Today we speak about the status of ‘most-favoured nation’ but whichever that nation has been in the past, it has always known the proper moment for acquiring the favour. The Venetians were more far-sighted than their desperate Byzantine antagonists (who were also allies when it suited either), or than their fellow-Catholic but semi-barbarous crusading allies, or even than their fierce rivals (no matter how Catholic), the Genoese. The perilous alliances that at separate times the Byzantine Emperors made with all three sets of Western Europeans, with the political, military, and trading favours each inevitably extorted, would some day lead to the destruction of Byzantium and the eventual triumph of Turkish arms. But none of this was yet to be foreseen. Except by the Venetians and they didn’t care. The day would come when they too would lose all their Eastern markets to the Turks, but for several centuries even then their motto remained ‘Essendo noi mercanti, non possiamo viver seza low.’

Back, though, to Corinth and the unrecorded miseries. In 1203 the immense criminality of the Fourth so-called Crusade had not yet happened—although Pope Innocent III was already gathering the armies of the West for their biggest communal adventure yet: supposedly the recovery of the Holy Places and the ill-defended Latin States of Palestine. In 1203 Greece was still (despite official or unofficial bloodsuckers) nominally independent: that is, ruled by Greeks.

But what did that mean in fact? In the case of the Peloponnese the Imperial administration vacillated between periods of negligence and outbursts of severity: a state of things well suited to the ambitions of whichever small local landowner could command more henchmen, money and weapons than his neighbour, and thus-either with the connivance of Imperial officials or when their backs were turned-become a bigger landowner.

It may be that this condition of administrative confusion and bizarre inconsequentiality contains the origin of the patron-client relationship that has plagued Greek history and daily life down to the present (with, maddeningly enough, intervals when the phenomenon has proved beneficent). It’s true, in this connection, that most of the big private and monastic estates were broken up in the 1920’s by Eleftherios Venizelos to accommodate the influx of a million and a half Greek refugees from Asia Minor into an already starving country; and as a result the archons, or big landowners of the Middle Ages to the early twentieth century, moved into town (if they hadn’t done so already), to limit their expertise to big business, shipping and politics. But today, fifty years later, many of the trappings of feudalism, and heavy doses of the feudal consciousness, still survive throughout the land in every walk of life.

A precursor of the feudal tycoon was Leon Sgouros, the strongman of Nauplia, who in 1203 seized Argos by ruse and Corinth by force-having also invited the Bishop to dinner, blinded him and, for good measure, tossed him over the cliffs. A man who lived a villainous life and died a hero’s death (in this part of the world a not infrequent syndrome), neither of which can have provided material benefit to his subjects, although his death was the last gasp of ethnic independence before a new invasion. Meanwhile he conquered Thebes, held it briefly, attacked Athens but was driven back by Michael Akominatos who, like a few other brave men after him, never gave up hope completely for his people in an evil hour.

A worse disaster loomed. The Fourth Crusade was being organized between the French, Germans, Burgundians, Flemish, English, Hungarians and Sicilians, with impetus from the Papacy, and the little matter of business between allied rivals being conducted by the Venetians.

Venice, with its long experience of East Mediterranean trade, and its intimate knowledge of the customs and riches of Byzantium, was in a position to dictate its terms—particularly when the crusading armies found themselves stranded on an island of the Venetian Lido, unable to pay the 85,000 marks for the fifty Venetian galleys that were to carry them ostensibly to the Holy Land. Pope Innocent may not have known exactly what the military and the businessmen were cooking up, but the fact remains that their joint plan was to his advantage: it was thanks to them that Catholic and Orthodox Christendom were to be united under his sole authority. Not that there was, essentially, any difference of purpose between Venice and its cohorts. The treaty binding the lot of them in one common venture contains the extraordinary clause: ‘First and foremost we must, by force of arms and with the invocation of the name of Christ, attack Constantinople.’

The Crusade began with the sack and destruction of the fellow – crusading city of Zara in Dalmatia. The Pope fulminated (‘Satan, the universal Tempter, has deceived you!’), excommunicated, changed his mind, took pity on the Crusaders, left the Venetians under his anathema, accepted the fait accompli, and, after the Crusaders gave up all pretense of recovering the Sepulchre from the Infidel, gave his blessing to an obscure Flemish count crowned Emperor in Sancta Sophia according to the Latin rite. In Greece, the Fourth Crusade has never been forgotten.

An indication of the insignificance of Athens at the time can be found in the treaty that partitioned in advance the entire Byzantine Empire between the Venetians and different sets of what were sanctimoniously termed ‘pilgrims’: at the very end of an elaborate list of towns and provinces occurs the item, ‘the district of Athens and the land round about Megara.’

As the administration of Greece was reorganized into a pyramidal structure of feudal Catholic kingdoms, principalities, duchies, marquisates, counties and baronies (where ‘they speak as beautiful French as they do in Paris,’ to quote the Catalan chronicler, Ramon Muntaner), a ducal palace was built into the Propylaea on the Acropolis, and the Venetians shrewdly confined their ambitions to a chain of listening-posts and trading colonies on coasts and islands. Leon Sgouros made a show of resistance against the Franks in Thessaly, then fled to the safety of his strongest fortress; there he held out against a Frankish siege lasting five years, and at the end of it committed suicide by riding his horse off the cliffs of Acrocorinth.

It is against this background of Western Europe’s Crusade against the Christians—although the Latin States in Greece had short brutal and pathetic lives, and there was a recrudescence of Byzantine power before the end—that we take our leave of two cities, that had shrunk to the sorriest of villages by 1460 when the Turks eliminated, throughout Greece, the last shreds of territorial independence and all but the memory of an empire