EDWARD LEAR

There once was an artist named Lear,

Who travelled and sketched far and near,

Known mainly for verse that’s nonsensically terse

He’s one and the same Edward Lear. — M.W.

Lear was born in 1812, the twentieth in a family of twenty-one children. A sickly child, he was entrusted chiefly to the care of his sister Ann, twenty-two years his senior, and it was she who gave him his first lessons in drawing. Otherwise he was essentially self-taught although much later, while in his late thirties, he briefly attended art classes at the Royal Academy Schools. Fortunately he was, despite weak eyesight, an acute observer and a superb draftsman, This gift is evident in his earliest ‘mature’ work, his detailed and lively drawings of the parrots in Regent’s Park Zoo, which he, himself lithographed and published at the age of twenty (Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots. London 1832). Their success brought him a number of commissions and his career might well have continued along these lines, but by 1836 he had decided that his real interest lay in the depiction of landscapes.

His health was never good and it took a turn for the worse in 1837 making it imperative that he seek a warmer and drier climate. The Earl of Derby, his patron and friend, offered to send him to Rome, and from then on much of Lear’s life was spent abroad. He became an inveterate traveller and, late in life, went as far afield as India and Ceylon, but it was always the Mediterranean countries, above all Italy and Greece, that attracted him most and where he felt most at home. In 1880 he visited England for the last time and the remainder of his life was spent in Italy. He died at his villa in San Remo in January 1888.

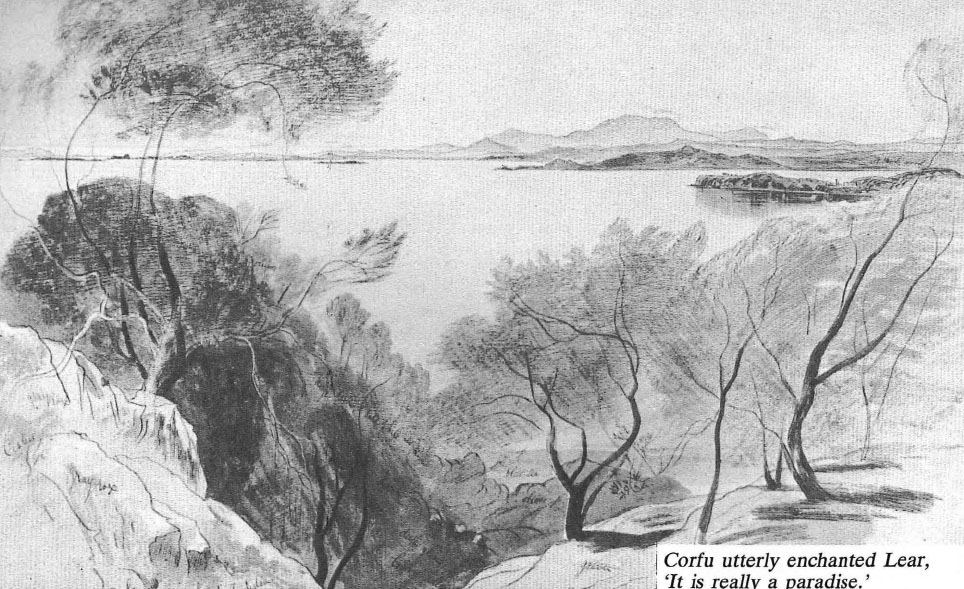

It was not until 1848 that he discovered Greece and the Eastern Mediterranean. For fifteen months, from April of that year until June, 1849 he was almost constantly on the move, exploring the Ionian Islands, Greece, Constantinople, Albania, and Egypt. Corfu, his first port of call, utterly enchanted him. ‘It is really a Paradise,’ he wrote his sister Ann, and on all his later visits to Greece, in 1856 – 1858 and in 1861 – 1864, its was always to Corfu that he returned, either for months of residence or as a base for further excursions to the Ionian Islands, to continental Greece, and finally, in 1864, to Crete. It was also in Corfu, in 1856, that he found Giorgio Kokali, his faithful Suliote servant, who was to remain with him 27 years, until his own death in 1883, and to accompany him on all his arduous travels.

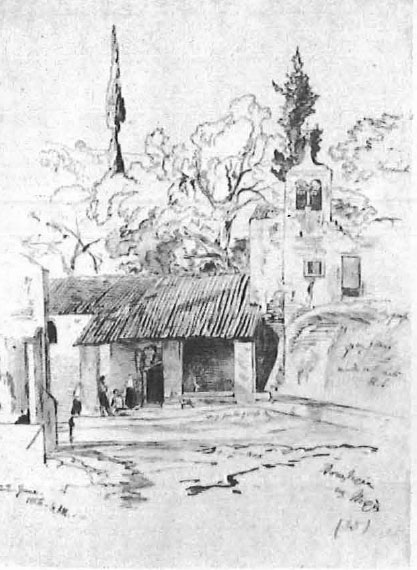

The years spent in Greece, or in and out of Greece, were among the happiest in his life and fortunately, even apart from his letters and diaries (still mostly unpublished) we have a partial record of his experiences and activities in those years. First and foremost there are his innumerable sketches. The Gennadius Library alone has about 200 of these, and while this is perhaps the single largest collection of those done in Greece their holdings must still be only a fraction of the total. There are also, of course, his finished oil paintings and water-colours, developed from the sketches, but in many cases executed much later. And finally there are two volumes published by him, each containing twenty lithographs.

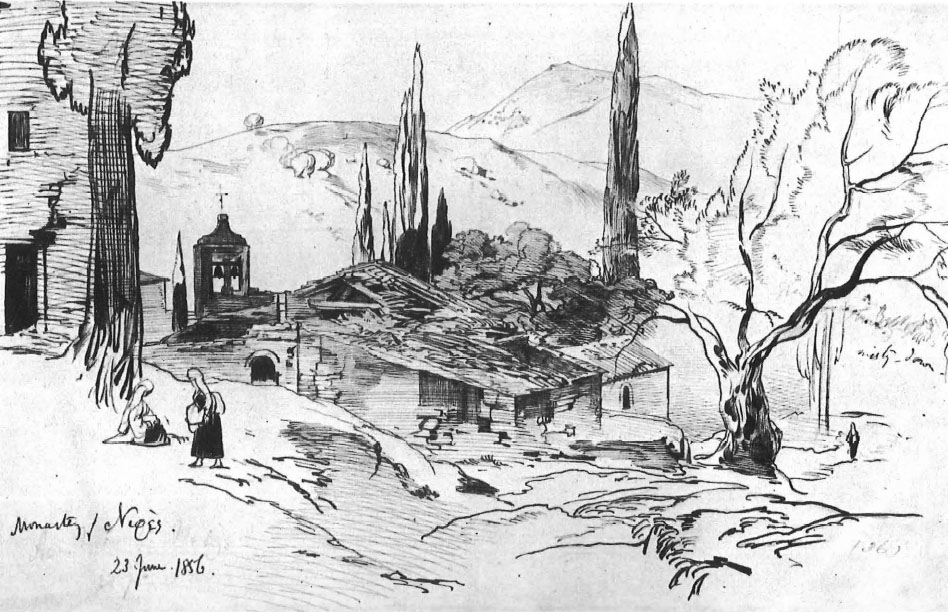

Journals of a Landscape Painter in Albania, etc. was published in London in 1851 and Views of the Seven Ionian Islands… drawn from nature and on stone in 1863. The latter volume is a picture book, comparable to those that he had producted earlier in Italy, containing only the lithographs and a brief explanatory text of each scene. The Journals is a real travel book (his first), and gives a lively and entertaining account of his travels. It was an immediate success and a second edition — retitled Journals… in Albania, Illyria, etc. — was issued in the following year. For the modern reader, however, the title — even in its expanded form — is somewhat misleading. Turkey-in-Europe would have been more accurate geographically, for although Albania takes pride of place in his narrative the modest ‘etc.’ is forced to serve as cover for Macedonia, Epirus, Thessaly, and part of southern Yugoslavia!

The actual narrative comprises two separate trips, one made from 9 September to 12 December, 1848, and the other from 24 April to 9 June, 1849. One can only regret that he omitted — for reasons unknown — the first half of the second journey when he travelled from Patras through the Morea, on to Athens, and thence to Levadia and Delphi. It would have been interesting to compare his account of travel in Othonian Greece with his experiences in the Turkish provinces to the north. And by an odd circumstance the Gennadeion collection has over 40 sketches dated from 9 March to 18 April, 1849, and only one (a recent gift) from the two northern excursions.

For Lear travel was not a luxury, done for pleasure, but a necessity of his trade, and the conditions under which he travelled were often difficult in the extreme. Food and lodging were undependable, the roads or stony tracks deplorable. As a rule he went on foot, preferring that to the discomfort of primitive saddles. Vermin made his nights an agony and it could be even worse when he was forced to sleep in a stuffy attic amid the stench of silk-worms. Yet he persevered and on the whole enjoyed, at least in retrospect, the trials of travel.

Everywhere he went Lear sketched industriously and the most important items in his gear were his drawing-pads, as essential to him as the camera to an avid traveller today. He rose at dawn and often made a drawing before breakfast. Along the road he stopped to sketch whever he found a view that was sufficiently ‘picturesque.’ His last sketch of the day was sometimes done at twilight, after reaching his destination. For 24 May 1864, the first day of a short tour south from Khanea in Crete that he and Giorgio made alone — without a guide or even a beast of burden to carry their supplies — we have, in the Gennadiuc Library, the complete product of his day’s work. As usual the sketches are dated, even to the hour: 5 a.m., 8 a.m., 9 a.m., 9:30 a.m., 11:30 a.m., 1 p.m., 6 p.m. Yet on this day, despite the many halts, they walked some 25 kilometres, much of it up hill and down hill!

As this record shows, Lear worked rapidly. His usual procedure was to sketch the scene in pencil, adding notes as to colour, flora and fauna, and anything else that interested or amused him. Some of the drawings have on the margin of the sheet a miniature layout of the scene, usually with a border added and the notation ‘totality,’ evidence of the care with which he planned his pictures. The notes, replete with eccentric spellings and Lear’s typical whimsicality, add immensely to our enjoyment: ‘Time and Assfiddle’ (thyme and asphodel); Ά depth full of sheep, goats and other vegebles’ (with ‘gotes’ written below a series of goat-like squiggles); ‘Hills purply gray russet greeny’; ‘Earwigs!’ and again, ‘Tortoises!!!’ One of the Cretan scenes has an unfinished limerick written below a tiny figure in the near distance:

There was a young person of Crete

Whose toilet was far from complete.

Occasionally, too, he used a system of numerals to indicate values; thus for a series of distant hills: Ί. (Mount) Ida pale. 2. Less so. 20. much nearer and deeper. 40. green begins.’ And at times he waxes lyrical: ‘Tone, after sunset, awful dark (& the sun fell, & all the land was dark.)’

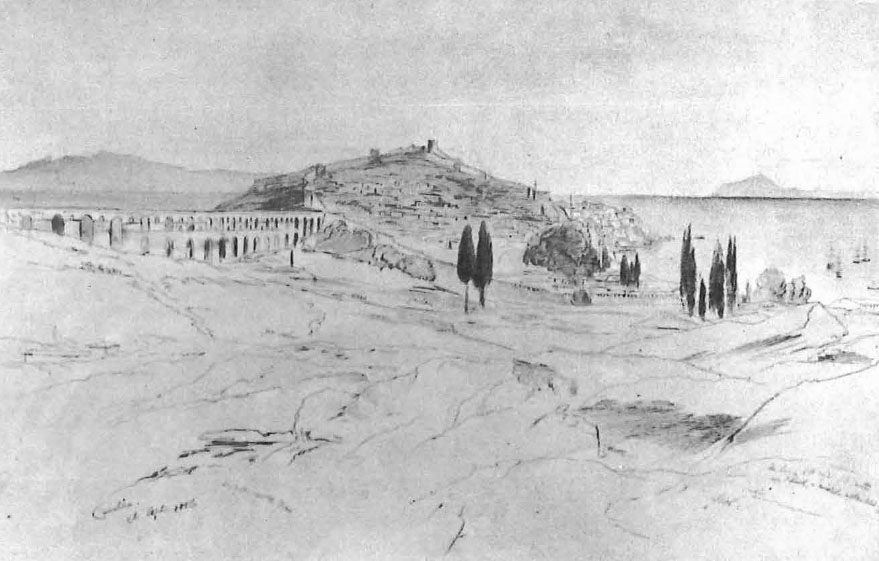

Later on, when not otherwise engaged, Lear would ‘pen out’ his drawings, going over all the pencil lines in ink and even copying the notes. This might be as much as seven years later, as he himself noted on one drawing, but even a short lapse of time might leave him uncertain of his original intentions. On a lovely view of Cavalla, dated 26 September, 1856, the shape of the castle evidently disturbed him. He penned out the contour that seemed most suitable and wrote on the bottom of the sheet, for future reference, a note: ‘The lines to the right of the castle are, I think, a mistake, not rubbed off.’

The final stage was to add some colour, with rare exceptions merely a light wash, just enough to suggest (with the notes) the colour and tones for a finished picture. These sketches, therefore, are not true water-colours, painted directly in colour. Nor are they pictures that Lear himself would have exhibited publicly or offered for sale. Rather they are memoranda to himself, models to be used if he decided to execute a formal painting or lithograph, samples, so to speak, that he could show to a prospective client who wished to commision a picture of, say, Delphi or Amalfi. Lear could then bring out the proper portfolio and say: ‘Here are my sketches of the place. See if any of these please you.’

Considering Lear’s productivity, the accumulated sketches of a lifetime must have amounted to some thousands. He bequeathed all of them, together with his other pictures and all of his books and papers, to his longtime friend, Franklin Lushington. Lushington gave a number of the pictures to Lear’s relatives and most of the rest, one must suppose, were stored away in some attic or lumber-room. There they remained for forty years.

After his death, Lear’s reputation as a landscape artist waned rapidly and by the end of the century he was virtually forgotten except as the author of nonsense verses. And, indeed, his art had never been popular, even though he had exhibited regularly at the Academy. The fact is that his ‘major’ works, especially his large oil paintings, are not very good, and even his finished water-colours, though attractive and gay, are more interesting for the scenes themselves than for their artistic value. However precise, topographically accurate, and detailed, they all tend to seem somewhat laboured.

His on-the-spot sketches, on the contrary, are vivid, lively, and apparently spontaneous although the spontaneity is that of a skilled craftsman and the facility of line is well disciplined, the product of keen observation and long practice. The sketches have an immediacy that the reworkings somehow lack. At his best — and many of the Greek sketches are among his best — he ‘captures’ the contours of the landscape and, with the greatest economy of line, makes up feel the contrast of plains and hills, the depth and distance of successive mountain ranges receding into the background.

Forty years after Lear’s death, when his repute as a painter was at its nadir, the two daughters of Lushington decided to get rid of the masses of ‘worthless’ paintings and drawings stored away. The market was suddenly flooded with Lears and for the first time his sketches became known to the general public. It was with their discovery that the re-assessment of his artistic abilities began. Little by little his reputation rose. The esteem in which he is held today is far greater than he ever enjoyed in his lifetime.

Early in 1929 a London dealer came upon a number of fine sketches of Greece while sorting out a large collection of the Lear drawings. It occurred to him that His Excellency Joannes Gennadius, the retired Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary of Greece at the Court of St. James’s (1910 – 1918) and founder of the Gennadius Library of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (dedicated in 1926) might be interested. He took them around for the elderly gentleman to see and Mr. Gennadius was enchanted with them.

Mr. Gennadius at once wrote to Professor Edward Capps, chairman of the Managing Committee of the American School of Classical Studies. The pictures, he wrote, would be a great addition to the Library in Athens, but he could not, at the moment, pay for them out of his own pocket. Would Professor Capps authorize him to purchase them on behalf of the School? If so, would he please cable, as he had only a two-week option? Three weeks later he received a letter from Capps’s secretary at Princeton University. The professor, she said, was off on a lecture tour and she had no way of reaching him. Finally, a week later, the cable came, ‘Buy.’ The pictures were still available and the Library thus acquired 192 of the Lear sketches for the sum total of £25, approximately a half-crown (or 65 cents) apiece. Then years later, from the same dealer, the Library purchased 14 others — in pen and pencil only, without colouring — at prices ranging from 10 to 30 shillings each. The market was rising. It has continued to rise and at present values our modest collection would probably fetch more than Edward Lear received in his entire career as an artist. He would, no doubt, be astonished at his belated success but pleased, too, that some of his Greek sketches had returned to the country that he loved so much. And, for us, ‘How pleasant to know Mr Lear.’

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Journals of a Landscape Painter in Albania, etc. has been reprinted under the title Edward Lear in Greece: Journals of a Landscape Painter in Greece and Albania, 1965. Biography and Criticism: Angus Davidson, Edward Lear, Landscape painter and nonsense poet, 1938. Philip Hofer, Edward Lear as a landscape draughtsman, 1967. Vivien Noakes, Edward Lear: the life of a wanderer, 1968.

Edward Lear’s drawings are from the Gennadius Library’s collection now on exhibition at the National Gallery. They are reproduced here with permission.